Owning History — A report from the Barry Halper baseball memorabilia auction at Sotheby’s, by Allan Wood, author of 1918: Babe Ruth and the World Champion Boston Red Sox

Owning History

By Allan Wood

In “Deep Blues,” music historian Robert Palmer wonders, how much meaning “can be hidden in a few short lines of poetry? How much history can be transmitted by pressure on a guitar string?”

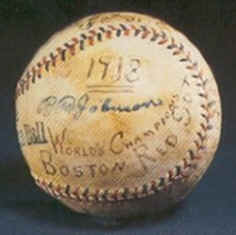

I thought of those words recently while holding a red- and blue-stitched baseball at Sotheby’s auction house in New York City. The ball’s half-faded signatures — George Whiteman, Wally Mayer, Everett Scott, Amos Strunk — had been inked almost exactly 81 years ago, when the ball was passed around the Boston clubhouse after the Red Sox won the 1918 World Series.

I thought of those words recently while holding a red- and blue-stitched baseball at Sotheby’s auction house in New York City. The ball’s half-faded signatures — George Whiteman, Wally Mayer, Everett Scott, Amos Strunk — had been inked almost exactly 81 years ago, when the ball was passed around the Boston clubhouse after the Red Sox won the 1918 World Series.

Having written a book about Boston’s last baseball champions, I felt a kinship with those nearly-forgotten men. The ball felt alive, as though it might explode in my hand or whisper to me some private revelation. Even after it was safely back in its locked case, I continued staring at it, burning its image in my mind. Babe Ruth and I both held that ball. As one small item among the 2,500 culled from Barry Halper’s mammoth baseball memorabilia collection, ready for auction, the ball would have a new owner within the week. Would it be me?

The auction had caught my eye because I’d been thinking about nostalgia and collecting, as integral to baseball as hot dogs and heartache. During a public exhibition of Halper’s items, I was entranced by a huge wall of baseball cards — the colorful paper rectangles forming a dazzling mural — and I thought of my own collection.

The card bug bit me when I was 11 years old, and I was soon buying and trading with friends, studiously arranging the cards in numerical order. I kept them in shoeboxes or, if l was lucky enough, the actual Topps display box. From the beginning, I was a completist, striving to get the entire 660-card set. I loved flipping through those handfuls of cardboard, the soothing flow of unbroken numbers.

That mentality was also apparent in my chronological piles of Spiderman comics and the issues of “Sports Illustrated” in my closet. The items I accumulate as an adult have changed (and sadly, I sold my cards in the early ’80s), but I haven’t shed my selective obsessiveness.

Now, for example, I’ll try to track down everything Lester Bangs and David Foster Wallace have written, clip articles about the seedier side of 19th Century Manhattan, or buy yet another bootleg of the Rolling Stones’ 1972 tour. My urge to collect took a new turn when I discovered online auctions and snapped up several Red Sox scorecards from the late ’70s, when I began following the team.

My collecting has always been private and idiosyncratic and thus, I assumed, unlike the pursuits of most memorabilia-hunting fans. What could I have in common with them? I don’t believe in judging an item’s worth by its monetary value, I’m unimpressed by trendiness or hipness, and I despise the incessant drum-beat of commercialism intruding on my personal hobby. I collect what I like.

People love to say, “I was there,” to announce that they experienced the actual, authentic moment. That 1918 baseball had been there — in the Fenway Park locker room, perhaps even used in that series-clinching game. It was undeniably authentic. A t-shirt, video, or other mass marketed “collectible” is only a commercial exploitation of an event; for me, it has none of the allure of authenticity. And my attraction to that baseball was also personal; the men who had signed it had become part of my life. A ball signed by, for example, the 1924 Red Sox wouldn’t hold the same mystique.

But a personal bond to memorabilia can have a dark side, too. Every Halper item connected to the New York Yankees or Brooklyn Dodgers of the ’40s and ’50s drew intense interest, since so many collectors and fans grew up with those magnificent teams. I understand that recalling favorite players and past events might offer a welcome respite from present-day stress. But I also sense the implication that this was baseball’s “golden age” — and, by extension, that today’s athletes do not measure up. Evidence of this bias has made me judgmental and dismissive of many collectors, and sometimes of the entire industry.

When viewed through adult eyes, baseball’s universe is wildly complex, its ideals and goals intricate and often contradictory. This helps explain why so many fans believe the game was better during their childhoods. As kids, they watched games and studied box scores; larger issues — race, economics — never crossed their minds and, indeed, were often ignored by the press altogether.

As time went on, a child’s favorite players became idealized as their glorious achievements were recounted again and again. But media coverage in the 1940s looked little like that of today. These days, players’ personal lives are deemed newsworthy and even the brightest stars have their worst moments exposed over and over on incessant highlight shows. How could those older heroes not appear flawless, even godlike, by comparison?

But let’s face it — Joe DiMaggio misplayed fly balls, Bob Feller got knocked out of the box, Jackie Robinson was caught trying to steal a base, and Ted Williams struck out with the game on the line.

Players’ personalities were no more exemplary back then either. The 1990s media tells us Barry Bonds is aloof and selfish, but if you’re looking for a role model, would you choose Bonds or Mickey Mantle?

And if we compare surly outfielders (a list of “The Century’s Most Unapproachable Lockers,” perhaps?), there are some surprising similarities between Albert Belle and Joe DiMaggio. Both could be moody, distant, acerbic. Reporters in DiMaggio’s day knew to stay away at certain times, but Belle is unlucky enough to play at a time when personality is often scrutinized as closely as performance.

Lost in reveries of baseball’s “golden age” is the brutal fact that for many of those years, only white men were allowed on the field. The deep stain of baseball’s racism often goes unmentioned when we hear stories of the glories of past generations.

Also glossed over is the long history of unfair (now illegal) labor practices. Fans speak in reverent tones about the low salaries in the “good old days,” somehow equating those paltry incomes with a deeper, more sincere love of the game. Not only were those guys better players, but they never griped about money — why, they would have played for nothing!

DiMaggio, again, provides a perfect counter-example. Our current image of the elegant Yankee Clipper tells only part of the story. His perennial salary disputes and spring training holdouts gave sportswriters ample opportunity to criticize the young player’s attitude. Taking their cue from the press, Yankee Stadium fans booed DiMaggio for months.

This selective editing of history — this myth-making — is what I have always imagined to be the mindset of most collectors. So I looked down on them, believing we had nothing in common. After a few days at Sotheby’s, I grew annoyed by and began mocking the wealthier bidders. Yet all the while, I craved that 1918 ball and continued collecting scorecards and programs. I started to worry. Was I hypocritical? Was I succumbing to the same rose-colored notions that so irritate me in others? Was I guilty of behavior I despise?

During a break in one of the sessions, Darrell O’Mary, a collector and dealer from Atlanta, sheepishly admitted to me that he went way over budget on a Christy Mathewson lot that included a gorgeous silver trophy awarded to “Big Six” after winning the 1911 World Series. When I asked O’Mary about his attachment to the Hall of Fame pitcher, he said, “I’ve always wanted a Mathewson item and I didn’t know how else to get one.”

At first, it didn’t seem like much of an answer. Only later, when I learned that the winning bids on 85 percent of the Halper items were higher than the expected price — in some cases, as much as ten times higher — did I realize O’Mary’s modest explanation was just honest.

If collecting strengthens our passions, soothes us or enhances our memories, then market value becomes irrelevant. That’s why O’Mary kept bidding past his limit — and it’s why I was prepared to spend several thousand dollars I didn’t have for a baseball signed by a group of men I have grown so fond of. As I thought more about these emotional connections, I understood a bit more — and realized I should scoff a bit less — about why people collect the things they do.

The Red Sox of the late ’70s meant a lot to me. I loved following them by radio every night and I want to remember those fond memories. But does that make me nostalgic? I don’t think so. The joy (and misery) I took from those teams was a huge part of my life, but I’m not idealizing those players or pretending those were the best of times. My baseball mementos are like old family photos or a tattered stuffed animal — tangible connections to the past. I realized that’s what many of those other collectors are searching for, too.

And that 1918 ball? Six days after I first held it, a flurry of pre-auction interest pushed even the opening bid well beyond my limit. I never raised my paddle, never uttered a word, as the ball sold for $10,000. I hope its new owner values his prize.